Why A Box Jump Is Not A Plyometric

- Harrison Armitage

- Jun 30, 2025

- 4 min read

“If you jump onto a box, you can call it plyometric…right?”

Not quite. That quick hop onto a box may feel explosive, but in the strict sense of sports science, most box jumps are ballistic jumps, rather than a true plyometric movement. Understanding the distinction isn’t just about technicalities; it’s information that can inform smarter training, reduce injury risk, and target the right adaptations.

Let’s break down what makes a movement truly plyometric and where the box jump fits into your toolkit.

What Exactly Is a Plyometric?

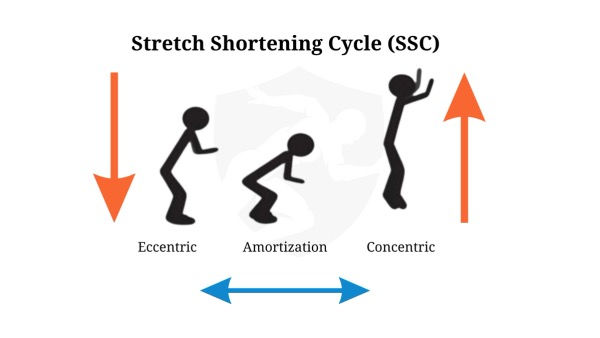

Plyometric exercises are designed to train the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC), which is the body’s ability to store elastic energy during a rapid muscle stretch (eccentric phase) and then release it during a quick contraction (concentric phase). This process is key to developing explosive power and efficiency in movements like sprinting, jumping, and cutting.

The SSC consists of three phases:

Eccentric preload – The muscle lengthens under load, storing potential energy.

Amortisation phase – A very brief isometric pause (must be under 250 milliseconds for the SSC to function effectively).

Concentric action – The muscle rapidly shortens, releasing stored energy and enhancing force output.

Research highlights that effective plyometric movements have short ground contact times (often under 200 milliseconds), high force outputs, and minimal countermovement delays (Flanagan & Comyns, 2008; Davies et al., 2015). Exercises like depth jumps, hurdle hops, and bounding are classic SSC-driven drills.

Why a Box Jump Isn’t a Plyometric

Key Phase | Depth/Drop Jump (Plyometric) | Typical Box Jump |

Entry | Step off box → fast ecc. landing | Small countermovement on floor |

Amortisation | < 250 ms before take-off | Often > 300 ms |

Take-off | Rebound immediately upward | Concentric push after slow load |

Landing | On floor (absorbs ecc. forces) | On top of box (ecc. forces greatly reduced) |

Most box jumps are performed from a standing start with a slow countermovement and a long ground contact time. The athlete then lands on an elevated surface, which reduces the intensity of the landing phase and limits the eccentric force absorption, a key component of true plyometric training.

Studies using force plates confirm that box jumps do not create the same reactive force demands as depth or drop jumps (Faulkinbury et al., 2010). As a result, the neuromuscular and tendon adaptations associated with the SSC are minimised.

This makes the box jump a better fit under the classification of a ballistic movement, rather than a plyometric.

So, What Is a Box Jump?

A box jump is more suited to fall under the catagory of a ballistic movement. These involve accelerating through the entire range of motion and projecting the body or an object into space.

In a box jump, the athlete loads into a countermovement and jumps with maximal intent. The landing is softened by the elevated surface, making it easier on joints and tendons. Box jumps are an excellent tool to train triple extension (hip, knee, ankle) and improve your vertical displacement (how much your centre of mass moves up and down).

Used effectively, box jumps can develop power, coordination, and timing without the high-impact stress of ground-based landings. However, they lack the rapid eccentric-concentric demand necessary to develop reactive strength, which is where true plyometrics shine (Cronin & Sleivert, 2005).

Why True Plyometrics Deserve a Place in Training

Incorporating plyometric exercises into a training program has well-documented benefits. A review by Markovic & Mikulic (2010) found that lower-body plyometric training can:

Increase vertical jump height by 4-9% over 6-12 weeks

Improve sprint times and change-of-direction ability

Enhance neuromuscular efficiency and motor control

Increase tendon stiffness, improving force transfer and reducing injury risk

These adaptations occur because plyometrics improve the body's ability to use elastic energy and enhance the stretch reflex. Over time, this leads to more powerful, efficient movements. Importantly, these gains are specific to exercises that truly exploit the SSC, not simply any explosive movement.

Practical Application For Your Goals

Goal | Best Tool | Focus |

Explosive take-off speed with minimal joint stress | Box jumps & other ballistic drills | Max intent; soft landing on box to reduce impact load |

Maximising power & reactive strength | Depth/drop jumps, hurdle hops, bounds | Emphasise short contact time and quick rebound |

Power endurance | Contrast or complex pairings (e.g., heavy squat into depth jump) | Program volume cautiously; full recovery between high-intensity efforts |

To optimise performance, both ballistic and plyometric exercises should be used strategically. Box jumps are great for developing explosive power in a low-impact way. Plyometrics are essential for enhancing reactive strength and improving the efficiency of high-speed movements.

Summary

Plyometrics involve rapid transitions from eccentric to concentric movement, using the stretch-shortening cycle to build explosive strength. These exercises demand speed, timing, and elasticity.

Box jumps are powerful ballistic movements that train concentric power and coordination, but they bypass the eccentric load and fast coupling phase that define plyometric training.

Use both wisely: ballistic movements like box jumps for safe power development, and true plyometrics for elastic, high-speed adaptations.

References

Behm, D. G., & Sale, D. G. (1993). Velocity specificity of resistance training. Sports Medicine, 15(6), 374–388.

Cavanagh, P. R., & Komi, P. V. (1979). Electromechanical delay in human skeletal muscle under concentric and eccentric contractions. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 42, 159–163.

Cronin, J., & Sleivert, G. (2005). Challenges in understanding the influence of maximal power training on improving athletic performance. Sports Medicine, 35(3), 213–234.

Davies, G., Riemann, B. L., & Manske, R. C. (2015). Current concepts of plyometric exercise. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 10(6), 760–786.

Faulkinbury, K., Stieg, J. L., Brown, L. E., Coburn, J. W., & Judelson, D. A. (2010). Potentiating effects of depth and box jumps on vertical jump performance in female collegiate volleyball players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(Suppl 1), 1–7.

Flanagan, E. P., & Comyns, T. M. (2008). The use of contact time and the reactive strength index to optimize fast stretch-shortening cycle training. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 30(5), 32–38.

Markovic, G., & Mikulic, P. (2010). Neuro-musculoskeletal and performance adaptations to lower-extremity plyometric training. Sports Medicine, 40(10), 859–895.

-3.png)

Comments